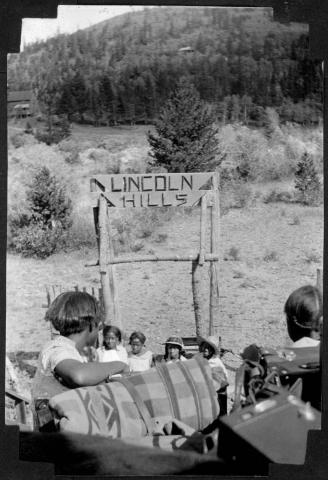

Lincoln Hills, located in Gilpin County, Colorado, was a vacation resort for African-Americans. Lincoln Hills was created in 1922 by E.C. Regnier and Roger Ewalt and was the only resort for African Americans west of the Mississippi River. Lincoln Hills served as a reprieve from segregation for middle class African-Americans in the 20th century.

SPORTS TALK ENT 1

By the 1920s, Denver had a thriving African American population living largely in the Five Points neighborhood. However, due to rising racial tensions in America and the presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Denver many African Americans faced hostility living in Denver. Denver businessmen E.C. Regnier and Roger Ewalt co-founded Lincoln Hills Development Company (LHDC) in 1922.

Regnier and Ewalt, both African American men, purchased over 100 acres 38 miles West of Denver. Regnier and Ewalt believed African Americans should be able to enjoy the mountain landscape and have a resort to escape the racial tensions of Denver. The men sold small land plots to African Americans which were usually 25 ft by 100 ft and had a price ranging from $5-$100. Many plots were used as campsites, however some families built rustic cabins. Regnier and Ewalt sold over 600 plots of land to middle class African American families who were located all across Colorado.

Get Ready Boxing Is Back!

Coming up on the Focuz TV One Network

The Interview of the year LIVE IN THE BULIDING KHALID SMITH AKA LID | SMITH stay tuned..

Lincoln Hills grew in size throughout the early 20th century and came to serve as renowned mountain resort for African American families. The resort served as the location for Camp Nizhoni, a YMCA girls camp that served African American women and girls who were prohibited from attending other YMCA camps due to segregation. Memoirs from Lincoln Hills describe the picturesque mountain landscape and the camaraderie that formed between many African American families who would return to the resort annually. During the Great Depression many African American families were forced to abandon their annual vacation plans. Moreover, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 allowed for the integration of African Americans into White resorts and clubs, thus Lincoln Hills had less of an appeal.[1][4] Lincoln Hills officially closed in 1966.

In 1980 Lincoln Hills was placed on the National Register of Historic Places due to the unique opportunity it afforded African American families.

In 2007, Matthew Burkett purchased the resort to preserve it. Currently, the non-profit organization Lincoln Hills Cares operates youth and family programs at the resort to expand access to the outdoors to African American and Latino families in the Denver region.

Lincoln Hills

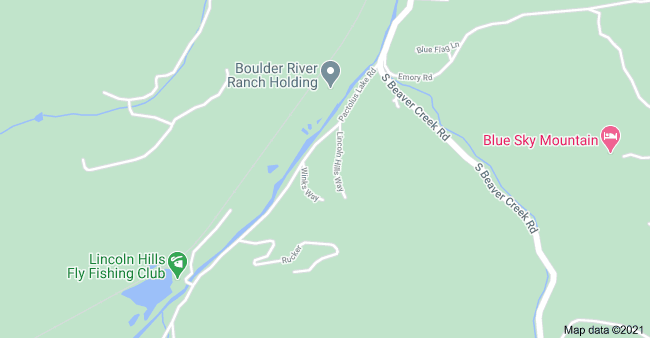

Located along South Boulder Creek about ten miles due west of Eldorado Springs and an hour’s drive from downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was established in the 1920s as one of a small handful of black resorts in the United States and the only one west of the Mississippi River. Easily accessible by car and train, the resort was a thriving vacation destination for four decades, until its main hotel and tavern, Winks Lodge, closed in 1965 and civil rights legislation opened new opportunities for black vacationers. Today descendants of original cabin owners continue to visit their properties at Lincoln Hills, and the area is also home to a private fly-fishing club and a nonprofit organization that provides outdoor experiences and education to veterans and youth.

Origins and Development

The Great Migration of the 1910s–20s is often seen as a movement of African Americans from the South to the North, but it also resulted in the growth of black communities in the West, including Colorado. By the 1920s, Denver had a strong and vibrant black community centered on the Five Points neighborhood, which had several thousand black residents. Most worked as porters, waiters, barbers, and domestic servants (the main jobs open to them at the time), but the community also contained a growing business and professional class. Yet as it became larger and more prosperous, Denver’s black community faced increasing hostility in the form of racially restrictive housing covenants and a resurgent Ku Klux Klan that claimed 50,000 members across Colorado, including prominent local and state officials.

This combination of prosperity and animosity stimulated the development of Lincoln Hills, the only resort in the Rocky Mountains that catered specifically to African Americans. The goal was to give blacks in Denver and across the country a place where they could escape the daily burden of racism and build an alternative to the racially segregated resorts that were prevalent at the time.

In 1922 Lincoln Hills was established by two Denver businessmen, E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt. Tradition maintains that the men were black, but records indicate that white men with those names lived in Colorado at the time. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that Regnier and Ewalt were black men whose skin was light enough to allow them to move back and forth across the color line when necessary. In any case, by 1925, they founded Lincoln Hills, Inc. and divided the area into roughly 1,700 narrow lots. Measuring 25 feet by 100 feet, the lots were advertised across the country to blacks interested in building summer cottages there. Lots were available for under $100 (with fairly easy financing: $5 down and $5 per month) and could be reserved by mail. By 1928, about 470 lots had been sold, half to people from Colorado and half to prospective vacationers or speculators from other parts of the country.

The Great Depression, which started in 1929 and deepened in the early 1930s, put a sudden end to many Lincoln Hills dreams. Some families could no longer keep up with the monthly payments, and those who could (or had already paid in full) did not have the extra money to build a summer cabin. As a result, only a few dozen private cabins were actually constructed.

Vacationing in the Rockies

Even if many buyers lost their lots or never built cabins, Lincoln Hills still managed to thrive for several decades. Some families used their lots as campsites; others came up for day trips. Crucial to the success of Lincoln Hills was its easy accessibility by train as well as automobile. The Denver & Salt Lake Railway (after 1931, part of the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad) stopped twice near Lincoln Hills, making it possible to get there in less than an hour from Denver or stop for a few days in the middle of a cross-country trip.

FOCUZ DOT MEDIA | ABOUT THE PEOPLE

Activities and accommodations were available to people who did not own property at Lincoln Hills. Each summer from 1927 to 1945, several dozen young black girls attended Camp Nizhoni, where they spent two weeks hiking, swimming, and learning outdoor skills and biology. Named after the Navajo word for “beautiful,” Camp Nizhoni was operated by the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA as an alternative to the all-white YWCA camp at Lookout Mountain. The camp featured a two-story dormitory and a dining hall on land that the Lincoln Hills development company sold for only $10 after the Wheatley YWCA had leased it and successfully managed the camp for three years.

Most important for the long-term popularity of Lincoln Hills was Winks Lodge, which opened in 1928. A three-story inn with six bedrooms in the main building and several outlying cabins, Winks Lodge was the brainchild of Denver businessman Obrey Wendell Hamlet, who went by the nickname “Winks.” The lodge and Winks Tavern, which opened later, were the center of activity at Lincoln Hills each summer and fall. Visitors could get a room, meals cooked by Hamlet’s wife, and outdoor recreation activities for $2–3 per day. Talented black musicians such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Lena Horne often stayed at Winks Lodge before or after playing clubs in Denver, and Hamlet also organized readings when writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston visited on their way to the West Coast.

EXCLUSIVE PHOTOGRAPHY AND FILM

End of an Era

Hamlet ran Winks Lodge until his death in 1965, which marked a turning point in the history of Lincoln Hills. His death and the subsequent closure of Winks Lodge coincided with the fundamental transformation of American society that made all-black resort communities like Lincoln Hills no longer necessary. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, it became possible for blacks to travel freely to resorts like Estes Park. With Winks Lodge closed and other resorts now open to all, Lincoln Hills was visited primarily by property owners whose families built cabins on their lots in the 1920s.

Focuz Dot Media The Most Diverse Multimedia Source Worldwide

Today

In 1980 Winks Lodge was added to the National Register of Historic Places at the state level of significance. In 2006 it was acquired by the Beckwourth Mountain Club (also known as Beckwourth Outdoors), a nonprofit organization focused on providing outdoor recreation opportunities for black youth.

In 2008 Denver businessman Matthew Burkett bought property at Lincoln Hills and established the Lincoln Hills Fly Fishing Club, a private angling club that built a clubhouse on the site of a former ice house. Burkett and Robert F. Smith also founded a charitable organization called Lincoln Hills Cares, which aims to preserve and publicize the history of the area by offering a variety of outdoor programs for veterans, children, and teens, including the Nizhoni Summer Equestrian Program for girls.

FUTURE CHAMPIONS

In late 2014, the National Register of Historic Places listing for Winks Lodge was elevated to the national level of significance for its role in African American history and enlarged to include more of the original Lincoln Hills resort community.

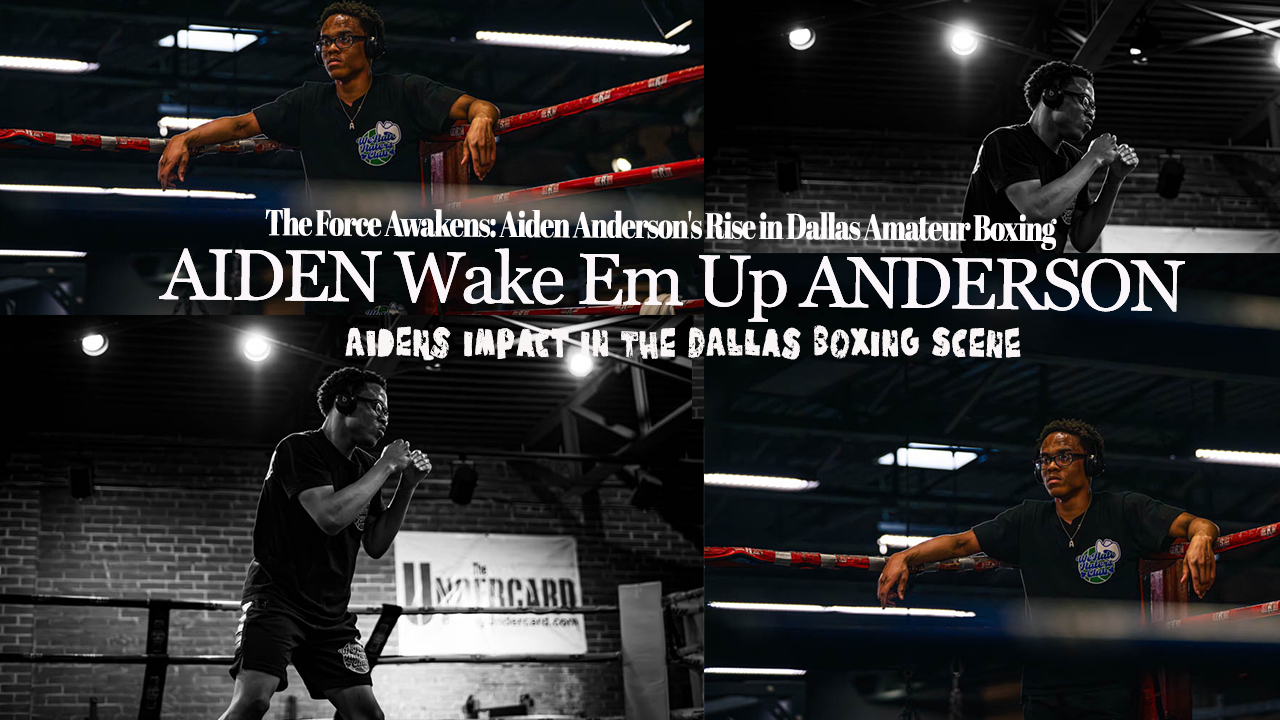

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing

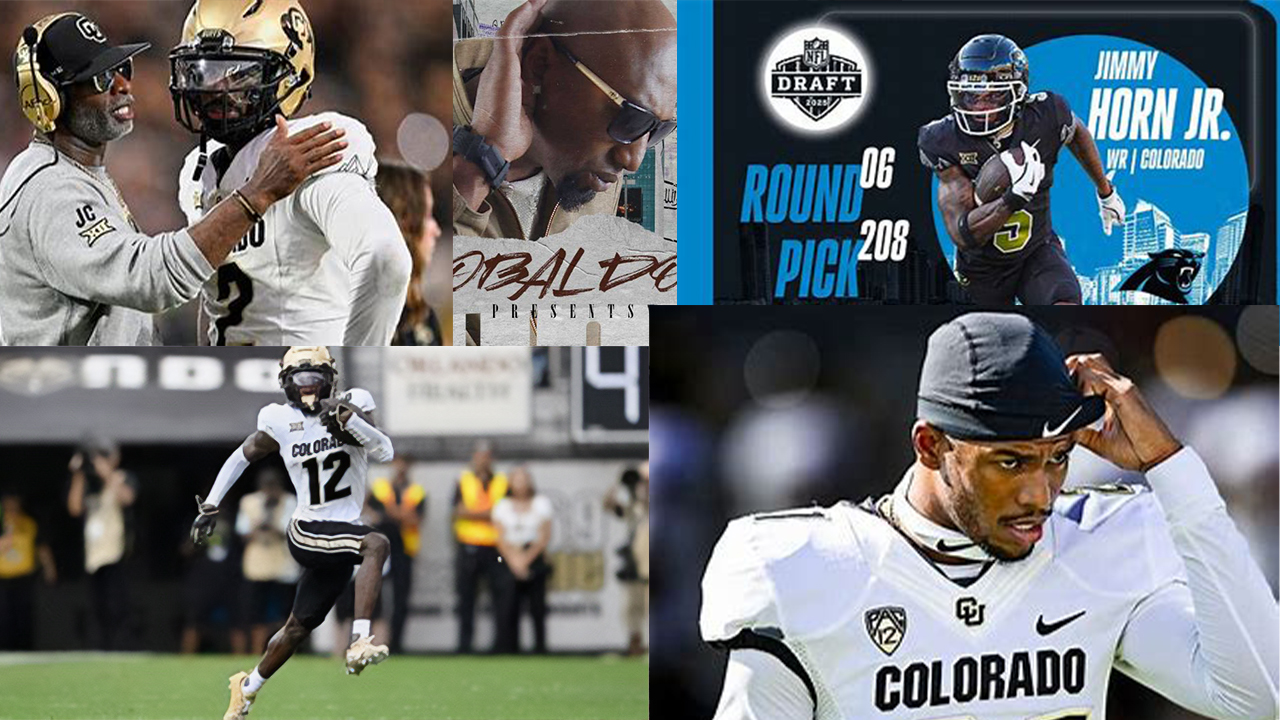

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing  Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more

Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more  Denver Public Schools has resolved to shut down seven schools, facing considerable opposition in the process.

Denver Public Schools has resolved to shut down seven schools, facing considerable opposition in the process.  The Real Spill Talk Show -Overwhelming Friends-

The Real Spill Talk Show -Overwhelming Friends-  SNACO

SNACO  Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert

Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert  Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities

Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities  Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants

Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants