In the first half of the 20th century, Clearwater Heights, Florida, was a Black neighborhood — thriving, proud and anchored by faith. But being in the segregated south, African Americans couldn’t stay at the White hotel, walk on the beach or swim in the bay. In death, they were laid to rest in segregated graveyards.

Those cemeteries were sacred ground until the ground became valuable. In the 1950s, headlines announced that the city of Clearwater made a deal on moving a “Negro” cemetery. Hundreds of African American bodies were to be reburied to make way for a swimming pool. A department store was planned for the site of another Black cemetery, where again, the bodies were to be moved. But O’Neal Larkin remembers, many years later, his first revelation that something was terribly wrong.

Why are graves dug to 6ft? Medical schools in the early 1800s bought cadavers for anatomical study and dissection, and some people supplied the demand by digging up fresh corpses. Gravesites reaching six feet helped prevent farmers from accidentally plowing up bodies.

“It’s not an imaginary thing that I seen. It’s what I seen with my own eyes,” Larkin told 60 Minutes correspondent Scott Pelley.

In 1984, Larkin, now 82 years old, watched a construction crew dig a trench through the site of a “relocated” Black cemetery.

“But I remember the parking lot where the engineers– traffic engineer was cutting the lines through,” Larkin said, “and they cut through two coffins. That was my first knowledge of seeing it because I walked out there, and I seen it myself.”

In 2019, the Tampa Bay Times reported many segregated cemeteries in Florida had been, essentially, paved. It was then that the modern city of Clearwater decided to exhume the truth.

Rebecca O’Sullivan and Erin McKendry are archeologists for a company called Cardno. Cardno was hired by the city to map the desecration.

“These individuals were loved. They were family members; they were fathers and mothers,” McKendry told Pelley. “And they were interred with love.”

“People deserve to be treated with respect,” O’Sullivan said. “That’s the most important thing.”

McKendry and O’Sullivan pushed ground penetrating radar over a segregated cemetery where an office site stands today. They found 328 likely graves, many, under the parking lot, perhaps a few under the building and more beneath South Missouri Avenue. 550 graves are in the cemetery’s record, McKendry and O’Sullivan found evidence of 11 having been moved in the 1950s.

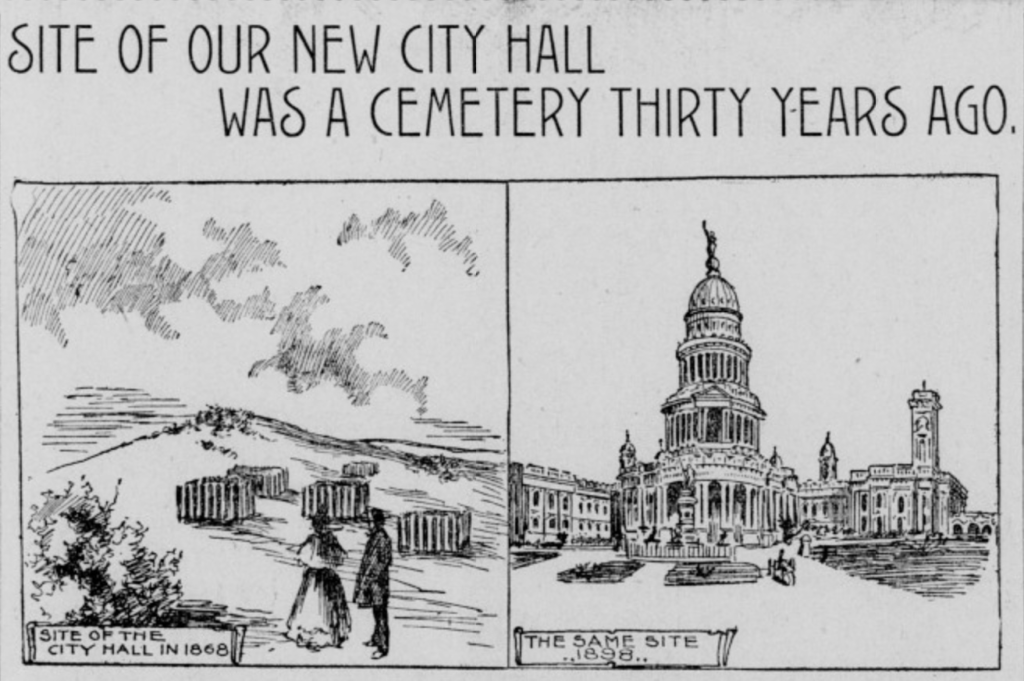

What are you walking on 8 Cemeteries Unearthed at Construction Sites

The people who lived before us are often just beneath our feet, even if their tombs are sometimes forgotten. Lost under urban development, they are rediscovered when a subway, building, or other structure claims the ground for progress. Here are eight burial sites that came to light in this unconventional manner.

1. SOLDIERS’ REMAINS IN ROME’S FUTURE SUBWAY

The construction of Rome’s subway has unearthed everything from a 2nd-century home decorated with mosaics and frescos to a 2300-year-old aqueduct. The San Giovanni station, slated to open in 2018, will feature displays of artifacts found during its excavation, such as Renaissance ceramics and the remains of a 1st-century agricultural fountain.

Back in 2016, extension work on Line C ran into a 2nd-century military barracks with 39 rooms, likely used by Emperor Hadrian’s army, as well as a mass grave of 13 skeletons. The dead may have been members of the elite Praetorian Guard, protectors of the Roman emperor. Investigations are ongoing, although officials have planned for the barracks to be incorporated into the station architecture. Its opening date remains in limbo as archaeological finds continue to slow its construction.

2. AFRICAN-AMERICAN NEW YORKERS UNDER AN OFFICE BUILDING

In 1991, construction of a federal office building revealed a colonial-era burial ground in Lower Manhattan. The graves, dating back to the 1690s, had been lost due to landfill and development, yet were identified as part of the African burial grounds that in the 17th century were located outside the old city.

Banned from interment in white cemeteries, free and enslaved Africans and African Americans had established a place to give respect to their dead, with an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 burials. Thanks to grassroots activism, including protests against continued construction, the site is now commemorated with the African Burial Ground National Monument, which opened in 2006.

It’s not the sole black cemetery to be buried under development in New York: The Second African Burial Ground, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, is located below today’s Sarah D. Roosevelt Park on the Lower East Side; and in East Harlem, a 17th-century slave burial ground, discovered by construction workers at a bus depot, awaits a planned memorial.

3. PLAGUE VICTIMS IN THE LONDON TUBE

Burrowing deep under London, the ongoing Crossrail commuter rail project has exposed obscure layers of the city’s past—and a treasure trove of history. Along with medieval ice skates and a Tudor bowling ball, archaeologists have identified two mass graves. One has 13 skeletons of people who probably died in the 14th century of Black Death (with DNA on their teeth still holding the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis); a larger site has 42 skeletons of victims of the Great Plague of 1665. The study of the Great Plague skeletons, excavated in 2015 by Museum of London Archaeology, similarly showed traces of the disease in their old teeth. (Luckily the bacteria is no longer active, so no need to dust off your plague doctor beak mask.)

While such “plague pits” have long been rumored—some urban legends say the London Underground had to curve to avoid messy heaps of bodies—study of the sites indicated that there was in fact great care taken with the deceased. The bodies were placed in individual coffins, giving them some dignity even in this hasty mass burial.

4. EARLY PHILADELPHIANS UNDER A FUTURE APARTMENT BUILDING

Sometimes, to borrow a line from Poltergeist, people only move the headstones when relocating a cemetery, and stray bones and coffins are left behind (digging up the dead is generally unpleasant work). That seemed to be the case with a graveyard unearthed at a construction site on Arch Street in Philadelphia in March 2017. The dozens of coffins that were discovered are believed to be part of the First Baptist Church Burial Ground, established in 1707 and supposedly moved to Mount Moriah Cemetery in 1859. The Mütter Institute spearheaded a crowdfunding campaign for analysis and reinterment of the bones, and volunteer archaeologists convened at the site, racing against time to map the grounds and remove the burials of more than 100 people. Their remains were carefully analyzed.

Archaeologists subsequently found the remains of more than 400 people at the site as construction went on in other areas. Building at the site continues, as does the grassroots-funded research on the bones (you can follow the team’s progress at the Arch Street Bones Project website).

Homes Built on “Lost” Florida Cemetery

What do they do with old cemeteries do they just put buildings over them?

5 PLAYGROUNDS BUILT ON CEMETERIES IN NYC

CHEESMAN PARK’S PAST LIFE…AS A CEMETERY

Unearthing Denver park’s creepy history

It’s just sad’: Conditions at a cemetery in Dallas have some families demanding answers

DALLAS — Some families are speaking out about conditions at a cemetery in southeast Dallas.

“It’s just sad,” said Tabrasha Remmy.

People who have loved ones buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery are complaining about high grass, tall weeds, overgrown areas, shifting headstones, grave markers sinking into the ground and damaged trees among other issues.

“It looks abandoned. It looks like no one cares about it,” Devin Venters said.

Venters said his family’s owned plots at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery more than four decades. He began voicing concern to staff about the conditions in the cemetery after a recent visit.

“I was pissed off about the way this cemetery was being held. Because it doesn’t look pleasing at all. I’ve never seen it look like this,” Venters explained.

Venters said staff wouldn’t give him any direct answers. He felt as if workers were brushing him off.

Venters took photos of the overgrown grass, damaged headstones and other problems he observed and shared them with his followers on social media. Many people also echoed frustration about conditions they also claim to have observed at that cemetery.

Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities

Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities  Yella Beezy Released on $750,000 Bond

Yella Beezy Released on $750,000 Bond  Global Don Breaking The Silence

Global Don Breaking The Silence  Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert

Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert  South Florida residents told to steer clear of ‘life-threatening’ flooding

South Florida residents told to steer clear of ‘life-threatening’ flooding  Camping 4 Beginners

Camping 4 Beginners  Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants

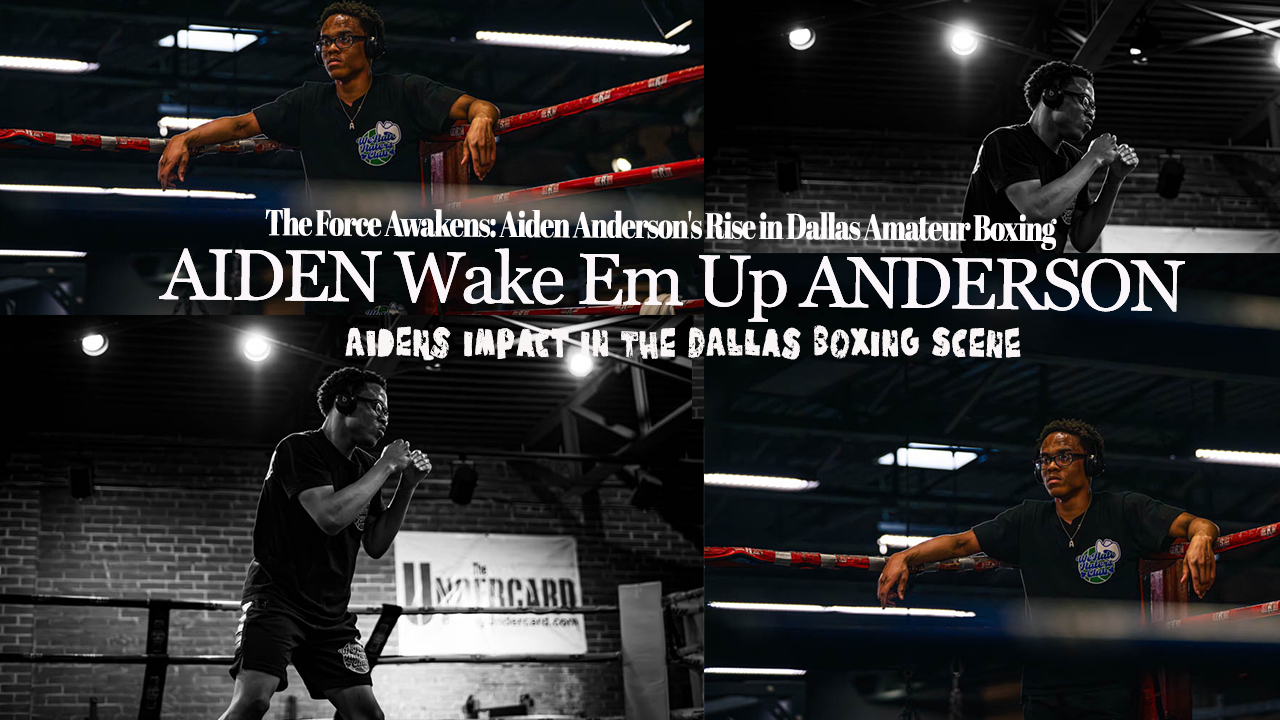

Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants  The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing

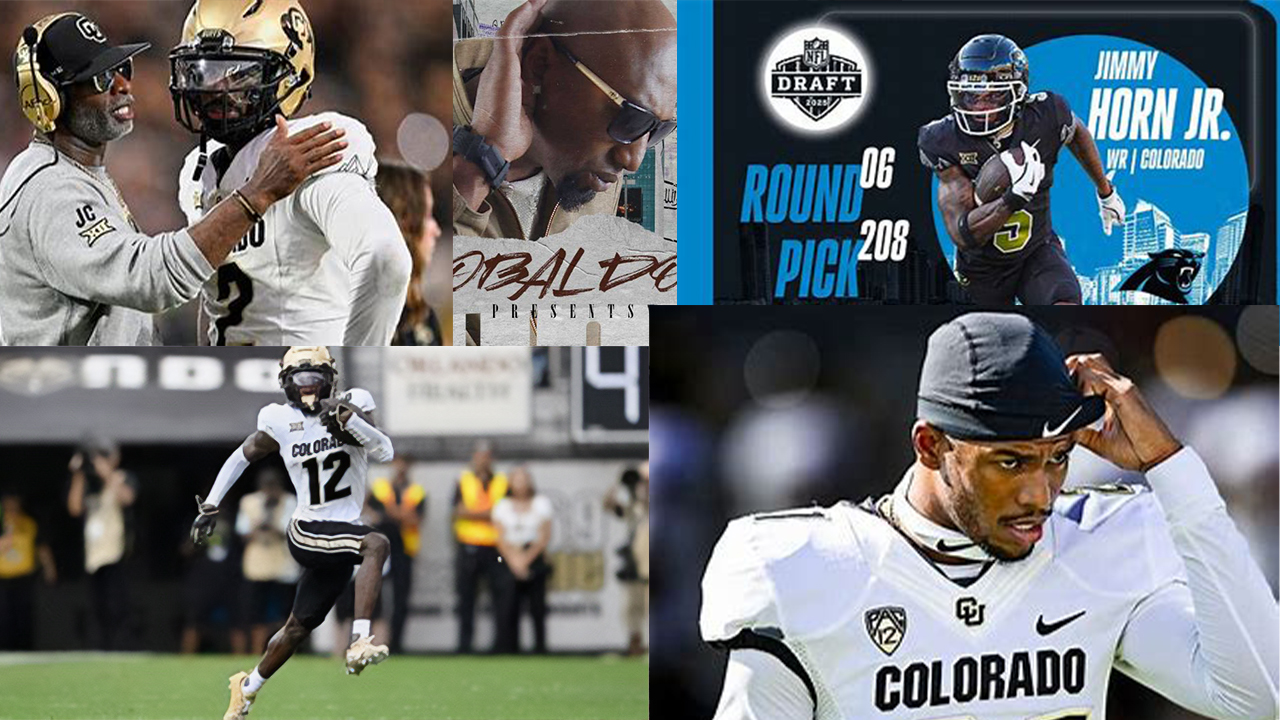

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing  Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more

Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more