Oklahoma City Oklahoma, Germaine Coulter, born into the unforgiving embrace of a rundown neighborhood in Germaine Coulter, born into the unforgiving embrace of a rundown neighborhood in Oklahoma City, never stood a chance. His life unfolded like a tragic symphony, each note echoing the discordant chords of fate.

From the moment he took his first breath, the odds were stacked against him. Poverty clung to his family like a relentless shadow. The streets whispered their secrets—the ones that whispered of hunger, desperation, and shattered dreams. Germaine’s crib was a hand-me-down, its paint chipped, its bars rusted. His lullabies were sirens wailing in the distance.

His mother, weary and worn, juggled multiple jobs just to keep food on the table. She had dreams once—of college, of a better life—but life had other plans. Germaine’s father? A phantom, a name whispered in hushed tones. He vanished before Germaine could form memories, leaving behind only a faded photograph and a void.

The school hallways became Germaine’s battleground. His shoes, frayed at the edges, carried him through the maze of lockers. The other kids, their backpacks bulging with textbooks, eyed him with suspicion. Germaine’s textbooks were borrowed, their pages dog-eared, remnants of countless hands that had come before.

Teachers tried to ignite sparks in his eyes, but the fire had long dimmed. Germaine sat in the back row, shoulders hunched, lost in the labyrinth of algebraic equations. Dreams of college? Laughable. Dreams required nourishment, and Germaine’s soul was malnourished.

He watched the affluent kids—the ones with shiny sneakers and family vacations. Their laughter echoed in the cafeteria, while Germaine’s stomach growled. He wondered what it felt like to have choices—to pick a future like selecting items from a menu. But for him, the menu was sparse: survival or surrender.

The streets beckoned. Germaine’s footsteps traced invisible paths—the shortcuts through alleys, the graffiti-covered walls. He learned the language of survival—the art of blending into shadows, of spotting danger before it spotted him. The corners whispered opportunities—petty theft, quick cash, a taste of power.

And so, Germaine Coulter became a chameleon. He wore different skins—sometimes the hustler, sometimes the beggar. His dreams? They morphed into mirages—elusive, shimmering on the horizon. The city swallowed him whole, its concrete veins pumping despair.

Choices? Germaine had none. The streets dictated his moves—the dice rolled, and he played the game. The corners traded innocence for survival. He became a ghost, haunting the same streets that birthed him.

In the end, Germaine Coulter was a footnote—a name etched on a police report, a statistic in a forgotten folder. He never had a chance, but perhaps, just perhaps, his story serves as a plea—a desperate cry for a world that offers more than scraps to those born on the wrong side of fate

, never stood a chance. His life unfolded like a tragic symphony, each note echoing the discordant chords of fate.

From the moment he took his first breath, the odds were stacked against him. Poverty clung to his family like a relentless shadow. The streets whispered their secrets—the ones that whispered of hunger, desperation, and shattered dreams. Germaine’s crib was a hand-me-down, its paint chipped, its bars rusted. His lullabies were sirens wailing in the distance.

His mother, weary and worn, juggled multiple jobs just to keep food on the table. She had dreams once—of college, of a better life—but life had other plans. Germaine’s father? A phantom, a name whispered in hushed tones. He vanished before Germaine could form memories, leaving behind only a faded photograph and a void.

The school hallways became Germaine’s battleground. His shoes, frayed at the edges, carried him through the maze of lockers. The other kids, their backpacks bulging with textbooks, eyed him with suspicion. Germaine’s textbooks were borrowed, their pages dog-eared, remnants of countless hands that had come before.

Teachers tried to ignite sparks in his eyes, but the fire had long dimmed. Germaine sat in the back row, shoulders hunched, lost in the labyrinth of algebraic equations. Dreams of college? Laughable. Dreams required nourishment, and Germaine’s soul was malnourished.

He watched the affluent kids—the ones with shiny sneakers and family vacations. Their laughter echoed in the cafeteria, while Germaine’s stomach growled. He wondered what it felt like to have choices—to pick a future like selecting items from a menu. But for him, the menu was sparse: survival or surrender.

The streets beckoned. Germaine’s footsteps traced invisible paths—the shortcuts through alleys, the graffiti-covered walls. He learned the language of survival—the art of blending into shadows, of spotting danger before it spotted him. The corners whispered opportunities—petty theft, quick cash, a taste of power.

And so, Germaine Coulter became a chameleon. He wore different skins—sometimes the hustler, sometimes the beggar. His dreams? They morphed into mirages—elusive, shimmering on the horizon. The city swallowed him whole, its concrete veins pumping despair.

Choices? Germaine had none. The streets dictated his moves—the dice rolled, and he played the game. The corners traded innocence for survival. He became a ghost, haunting the same streets that birthed him.

In the end, Germaine Coulter was a footnote—a name etched on a police report, a statistic in a forgotten folder. He never had a chance, but perhaps, just perhaps, his story serves as a plea—a desperate cry for a world that offers more than scraps to those born on the wrong side of fate.

Germaine Coulter, a name that echoed through the dimly lit streets of Oklahoma City like a haunting refrain. His life was a tapestry woven with threads of darkness and deceit, a tale that left scars on the souls of those who crossed his path.

Born into poverty, Germaine clawed his way out of the shadows, fueled by ambition and a hunger for power. His eyes, sharp as shards of broken glass, surveyed the cityscape—the neon signs flickering, the alleyways whispering secrets, and the desperate souls seeking refuge.

In the heart of the city, Germaine established his dominion. His empire wasn’t built on bricks and mortar; it thrived on the vulnerability of others. He was a puppet master, pulling strings that led to darkened rooms, where innocence was bartered away like cheap currency.

The whispers spoke of Germaine’s underground network—a web of vice, temptation, and forbidden desires. He wore tailored suits, the fabric concealing the sins etched into his skin. His fingers danced across the keys of encrypted phones, orchestrating transactions that left no trace.

But Germaine’s true power lay in the shadows he cast over the youth. High school girls, their dreams still fragile, fell into his snare. He promised them escape, whispered sweet lies of freedom. And they, desperate for a glimmer of hope, followed him willingly into the abyss.

Edmond Santa Fe High School became his hunting ground. The lockers held secrets—the scent of fear, the taste of betrayal. Germaine’s eyes lingered on the young faces—their innocence ripe for the taking. He groomed them, painted their dreams with shades of crimson, and sent them out into the night.

Brian Bates, a relentless private investigator, had seen enough. He knew Germaine’s game—the manipulation, the coercion. In 2018, he distributed flyers to Germaine’s upscale neighbors, branding him a pimp, a ring leader of a prostitution syndicate. The whispers grew louder, but Germaine denied them vehemently, his voice cracking with rage.

Yet Bates persisted. He watched Germaine, shadows merging with shadows. Two months of surveillance, and the truth emerged—an insidious plot involving high school girls forced to sell their bodies. Germaine’s reign was over; the curtain fell on his malevolence.

In the courtroom, Germaine’s eyes met Bates’s. The investigator’s promise echoed—prison awaited him. The gavel struck, sealing his fate. Thirty years—a lifetime behind bars. Germaine’s protests fell on deaf ears; the community breathed easier.

And so, Germaine Coulter faded into the annals of infamy. His legacy—a cautionary tale etched into the city’s memory. The streets whispered his name, a reminder that darkness could be vanquished, even when it wore a tailored suit.

What happened to Oklahoma City after Germaine was arrested?

After Germaine Coulter was arrested, the city of Oklahoma City grappled with the aftermath of his crimes. Here are some key developments:

- Sentencing and Justice:

- In September 2021, Germaine Coulter, Sr., aged 48, was sentenced to serve 30 years in federal prison for child sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit child sex trafficking. His accomplice, Elizabeth Andrade, was previously sentenced to serve 78 months for her role in the sex trafficking conspiracy.

- The court recognized the severity of their actions, which involved recruiting young girls for commercial sex work and subjecting them to threats and violence. The hope was that this lengthy prison sentence would prevent Coulter from exploiting more children and bring solace to the victims in their recovery.

- Community Impact:

- The revelation of Germaine Coulter’s crimes shocked the community. People grappled with the realization that such exploitation had occurred within their midst.

- Advocacy groups, law enforcement agencies, and community members rallied to raise awareness about child sex trafficking and to support survivors.

- Increased Vigilance:

- The case prompted heightened vigilance among law enforcement agencies, schools, and community organizations. Efforts to identify and rescue victims intensified.

- Organizations collaborated to prevent similar incidents and provide resources for survivors.

- Legal Precedent:

- Germaine Coulter’s trial set a legal precedent, emphasizing the severity of crimes against children. The court’s decision sent a strong message that such offenses would not be tolerated.

- Continued Awareness and Education:

- Oklahoma City continued to educate its residents about the signs of human trafficking and the importance of reporting suspicious activities.

- Schools implemented awareness programs to empower students and parents to recognize and combat exploitation.

- Long-Term Healing:

- The victims, often young and vulnerable, faced a long road to healing. Support services, counseling, and community programs were crucial for their recovery.

- Advocacy groups worked tirelessly to raise funds and provide resources for survivors.

In the wake of Germaine Coulter’s arrest, Oklahoma City grappled with the darkness that had infiltrated its streets. But it also rallied together, determined to protect its youth and ensure that justice prevailed.

Germaine Coulter’s arrest, Oklahoma City grappled with the darkness that had infiltrated its streets.

Note: Germaine Coulter’s case serves as a reminder of the ongoing fight against human trafficking and the importance of community vigilance.

The arrest and conviction of Germaine Coulter sent shockwaves through the community, especially among schools and parents in Oklahoma City. Here’s how they responded:

- Heightened Awareness:

- Schools and parents became acutely aware of the dangers of child sex trafficking and exploitation.

- Educational institutions initiated awareness campaigns, workshops, and training sessions to equip parents, teachers, and students with knowledge about the signs and prevention of such crimes.

- Vigilance and Communication:

- Schools encouraged open communication between parents, teachers, and students. They emphasized the importance of reporting any suspicious behavior or signs of exploitation.

- Parents were urged to maintain an active presence in their children’s lives, both online and offline.

- Safety Measures:

- Schools reviewed and strengthened safety protocols. They ensured that students had access to counselors and resources to discuss any concerns.

- Parents were advised to monitor their children’s online activities and educate them about safe internet practices.

- Community Support:

- Parent-teacher associations (PTAs) organized community meetings to address concerns and share information.

- Support groups for parents and survivors were established to provide emotional support and guidance.

- Collaboration with Law Enforcement:

- Schools worked closely with local law enforcement agencies. They shared information about potential threats and collaborated on preventive measures.

- Parents were encouraged to attend community policing events and engage with officers.

- Trauma-Informed Approach:

- Schools and parents recognized that survivors of exploitation needed specialized care.

- Trauma-informed counseling services were made available to affected students.

- Legal Education:

- Schools incorporated age-appropriate discussions about consent, boundaries, and exploitation into their curricula.

- Parents were educated about legal rights and resources available to victims.

- Empowering Students:

- Schools empowered students to recognize and resist manipulation. They taught assertiveness skills and self-defense techniques.

- Parents encouraged open dialogue with their children, emphasizing trust and support.

- Community Unity:

- Schools organized events to foster community unity. They celebrated resilience and emphasized that everyone played a role in protecting children.

- Long-Term Healing:

- Schools and parents acknowledged that healing was a process. They supported survivors and their families throughout their recovery journey.

In the wake of Germaine Coulter’s arrest, schools and parents united to create a safer environment for their children, vowing to remain vigilant and proactive against exploitation.

Students in Oklahoma City were deeply affected by the revelations surrounding Germaine Coulter’s crimes. Here’s how they reacted:

- Shock and Disbelief:

- When news broke about the exploitation of high school students, shockwaves reverberated through the hallways. Students couldn’t fathom that such darkness existed within their own community.

- Fear and Vulnerability:

- Fear gripped many students. They wondered if they had unknowingly encountered Germaine Coulter or been targeted by his network.

- Vulnerability seeped into their consciousness—the realization that exploitation could happen to anyone, even within the safety of their schools.

- Anger and Betrayal:

- Anger flared as students learned about the manipulation and coercion these victims endured. They felt betrayed by someone who should have protected them.

- The sense of betrayal extended beyond the immediate victims; it tainted the entire school environment.

- Unity and Support:

- Students rallied together. They attended awareness sessions, workshops, and assemblies to learn about human trafficking and how to protect themselves.

- Peer support networks formed, emphasizing vigilance and looking out for one another.

- Empowerment and Advocacy:

- Some students channeled their emotions into advocacy. They organized fundraisers, awareness campaigns, and events to raise funds for survivors.

- Empowered by knowledge, they vowed to be vigilant and report any suspicious activity.

- Trauma and Healing:

- The victims’ trauma resonated with students. They empathized with the survivors’ pain and resilience.

- Counseling services were in high demand as students grappled with their emotions.

- Educational Shifts:

- Schools adjusted their curricula. Students engaged in discussions about consent, boundaries, and recognizing signs of exploitation.

- They learned about legal rights and resources available to victims.

- Hope and Resilience:

- Amid the darkness, students found hope. They witnessed survivors’ strength and resilience.

- Art projects, poetry, and music became outlets for expressing their emotions and advocating for change.

- Long-Term Impact:

- Germaine Coulter’s case left an indelible mark on students’ lives. It ignited a commitment to protect themselves and their peers.

- They vowed to break the silence, ensuring that no one else would fall victim to exploitation.

In the aftermath of this case, students grappled with a harsh reality but also discovered their collective power to create change and protect one another.

Where is Germaine Coulter now?

Germaine Coulter, Sr., the man convicted of child sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit child sex trafficking, is currently serving his 30-year federal prison sentence in an undisclosed location12. His actions had a profound impact on the community, and his imprisonment serves as a reminder of the ongoing fight against exploitation and the need to protect vulnerable individuals

UNITED STATES v. COULTER (2023)

Defendant-Appellant Germaine Coulter, Sr., appeals his convictions for child sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit child sex trafficking. Exercising jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, we affirm.

I. BACKGROUND

A. Factual History 1

For many years, Mr. Coulter was a pimp in the Oklahoma City area. Upon release from a five-year state prison term in 2017, he conscripted an underage girl, “Doe 2,” to recruit a schoolmate, “Doe 1,” to perform sex work for him. He gave Doe 1 a ride home from school, proposed that she work for him, and promised her money and gifts in return. After Doe 1 expressed interest, Elizabeth Andrade, one of Mr. Coulter’s longtime sex workers, took pictures of Doe 1 in various stages of undress and sent them to Mr. Coulter. He forwarded the photos to potential clients with messages suggesting that Doe 1 would perform sex acts for money. Ms. Andrade also sent the photos to potential clients and used one of the photos to advertise Doe 1’s services online.

Doe 1 had sexual encounters with clients for money. Mr. Coulter gave her detailed instructions about how much she should charge and when to collect the money. He also told Ms. Andrade to teach Doe 1 how to perform various sex acts. Ms. Andrade took Doe 1 on a “call” with her, and both of them had sex with the client.

Around the same time, Mr. Coulter attempted to recruit another underage girl, “Doe 3.” He gave Doe 3 a ride home from school and asked whether she wanted to earn money by “prostitut[ing] [her]self with the other girls.” ROA, Vol. III at 864. Doe 3 told Mr. Coulter she would “think about it,” but she had no interest in working for him and never did. Id. at 867.

B. Procedural History

A grand jury indicted Mr. Coulter and later issued a superseding indictment charging him with (1) conspiring with Ms. Andrade to commit child sex trafficking, (2) child sex trafficking with respect to Doe 1, and (3) child sex trafficking with respect to Doe 3. The grand jury also indicted Ms. Andrade for conspiracy to commit child sex trafficking. She pled guilty.

The case against Mr. Coulter proceeded to a jury trial. The Government introduced testimony from (1) law enforcement agents who investigated Mr. Coulter; (2) Ms. Andrade and other women who had worked for Mr. Coulter; (3) Does 1, 2, and 3; and (4) the client who had the sexual encounter with Ms. Andrade and Doe 1. The Government also introduced into evidence Mr. Coulter’s cell phone records, which corroborated these witnesses’ testimony.

We note three occurrences during trial that are relevant to this appeal. First, the Government elicited testimony from two witnesses about the deaths of two women associated with Mr. Coulter—Elizabeth Diaz and Jamie Biggers. Defense counsel objected to some questions about Ms. Diaz’s death, arguing they implied that Mr. Coulter was responsible. The district court sustained the objection and forbade the Government from “rais[ing] an inference that [Mr. Coulter is] responsible for th[e] girl’s death.” ROA, Vol. III at 427. During closing arguments, the Government briefly mentioned Ms. Diaz, but did not suggest that Mr. Coulter had killed her.

Second, the district court appointed a guardian ad litem for each of the minors involved in the case. At one point during Doe 1’s testimony, defense counsel requested a bench conference and asserted that Doe 1’s guardian ad litem had mouthed “[y]ou’re doing a good job” to Doe 1 while she was on the stand. ROA, Vol. III at 690. The district court had not observed this conduct, but at defense counsel’s request, the court told the guardian ad litem to avoid signaling Doe 1 during her testimony. The court also delivered a curative instruction to the jury.

Third, the jury deliberated for about six hours before reporting it had reached a verdict. It filled out verdict forms finding Mr. Coulter guilty on Counts 1 and 2—the conspiracy charge and the child sex trafficking charge related to Doe 1—but said it was deadlocked on Count 3—the child sex trafficking charge related to Doe 3. When the district court polled the jury, one juror, Ms. Noland, said the verdict did not reflect her opinion and expressed that she did not want to return to the deliberations.

The district court recessed for the weekend. On Monday morning, Mr. Coulter moved for a mistrial based on these events with the jury. The district court denied the motion.

The judge then spoke with Ms. Noland in chambers. She said that she was willing to continue deliberating. The court next convened the jury and delivered an Allen instruction encouraging the jury to try to reach unanimity. After several more hours of deliberation, the jury again returned a guilty verdict on Counts 1 and 2 but reported it could not reach agreement on Count 3. All jurors confirmed their assent to the published verdict.

Mr. Coulter later moved for a new trial under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 33(a), asserting that (1) the evidence against him was insufficient to support the jury verdict and (2) the district court erred in admitting testimony about the deaths of Ms. Diaz and Ms. Biggers. The court denied the motion. It sentenced Mr. Coulter to 360 months in prison. This appeal followed.

We set out additional facts and procedural history as needed in reviewing the issues Mr. Coulter raises.

II. DISCUSSION

On appeal, Mr. Coulter argues:

A. The evidence was insufficient to support the guilty verdict;

B. The district court improperly admitted testimony about the deaths of Ms. Diaz and Ms. Biggers;

C. The behavior by Doe 1’s guardian ad litem was improper bolstering;

D. The district court erred in its post-trial interactions with the jury; and

E. The convictions should be reversed based on cumulative error.5

As discussed below, Mr. Coulter failed to raise a contemporaneous objection to preserve several of these issues. When a party fails to preserve an issue, we review only for plain error. United States v. Mullins, 613 F.3d 1273, 1283 (10th Cir. 2010). “A plain error that affects substantial rights may be considered even though it was not brought to the court’s attention.” Fed. R. Crim. P. 52(b). We provide a brief overview of plain error here.

Convictions for child sex trafficking

Under plain error review, the appellant bears the burden to “show the district court committed (1) error (2) that is clear or obvious under current law, and which both (3) affected [his] substantial rights and (4) undermined the fairness, integrity, or public reputation of judicial proceedings.” Mullins, 613 F.3d at 1283.

“In general, for an error to be [clear or obvious and] contrary to well-settled law”—the second prong of plain error—“either the Supreme Court or this court must have addressed the issue.” United States v. DeChristopher, 695 F.3d 1082, 1091 (10th Cir. 2012) (quotations omitted).

To establish that an error affects a defendant’s “substantial rights”—the third prong—the appellant must show “there is a reasonable probability that, but for the error claimed, the result of the proceeding would have been different.” United States v. Bustamante-Conchas, 850 F.3d 1130, 1138 (10th Cir. 2017) (en banc) (quotations omitted). An appellant facing “overwhelming evidence of his guilt” usually “cannot establish a reasonable probability” that an alleged error “affected the outcome of the trial.” See United States v. Ibarra-Diaz, 805 F.3d 908, 926 (10th Cir. 2015).

Finally, the fourth prong of plain error review—whether an error “seriously affects the fairness, integrity or public reputation of judicial proceedings”—is a “case-specific and fact-intensive” inquiry. Bustamante-Conchas, 850 F.3d at 1141 (quotations omitted). Generally, “the seriousness of the error must be examined in the context of the case as a whole,” and the error must be “the kind [ ] that undermines the fairness of the judicial process.” Id. at 1141-42 (quotations omitted).

Americas Most Wanted episode 26, sex trafficking. Mario Diaz is a notorious “Pimp” from OKC. Portrayed by Hip-hop artist from Miami, TSLaB.

A. Sufficiency of the Evidence

Mr. Coulter argues that the evidence was insufficient to support his convictions. In particular, he contends that Ms. Andrade and Doe 1 were not credible witnesses. Aplt. Br. at 38-39. We reject his argument and affirm.

1. Standard of Review

“We review [an] insufficiency-of-the-evidence claim de novo.” United States v. Benford, 875 F.3d 1007, 1014 (10th Cir. 2017) (quotations omitted). “Evidence is sufficient to support a conviction if, viewing the evidence and the reasonable inferences therefrom in the light most favorable to the government, a reasonable jury could have found the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.” Id. “In reviewing the evidence, we do not weigh conflicting evidence or consider witness credibility, as these duties are delegated exclusively to the jury.” United States v. Evans, 318 F.3d 1011, 1018 (10th Cir. 2003).

2. Analysis

The Government presented more than sufficient evidence to support Mr. Coulter’s two convictions.

a. Child sex trafficking

To convict Mr. Coulter of child sex trafficking, the jury had to find that Mr. Coulter:

(1) “by means affecting interstate commerce,

(2) knowingly recruited, enticed, harbored, transported, provided, obtained, or maintained [a minor] or benefitted in a venture which involved [a minor], and

(3) knew or recklessly disregarded the fact that [the minor] was younger than 18, and

(4) knew or recklessly disregarded the fact that [the minor] would engage in a commercial sex act.”

United States v. Brinson, 772 F.3d 1314, 1325 (10th Cir. 2014) (numbers added) (citing 18 U.S.C. § 1591(a)).

Elements (1), (2), and (4) – In addition to the testimony of Doe 1 and Ms. Andrade about the recruitment and preparation of Doe 1 for sex work, the Government introduced Mr. Coulter’s phone records, which contained (1) explicit pictures of Doe 1, (2) text messages soliciting clients for Doe 1, and (3) instructions directing Doe 1 to take money from clients in exchange for sex. Suppl. ROA, Vol. II at 16, 19-21 [Redacted]; ROA, Vol. III at 453-56. The Government also presented a client who had a sexual encounter with Doe 1 and Ms. Andrade in exchange for money. ROA, Vol. III at 731-32. This evidence was sufficient to establish that Mr. Coulter used means affecting interstate commerce to knowingly recruit Doe 1 to perform commercial sexual transactions and facilitated those transactions. A reasonable jury could find elements (1), (2), and (4) of child sex trafficking beyond a reasonable doubt.

Element (3) – According to both Ms. Andrade and Doe 1, Mr. Coulter first suggested that Doe 1 perform sex work for him while driving her home from high school. ROA, Vol. III at 443. Ms. Andrade also testified that she told Mr. Coulter that Doe 1 was a minor. Id. at 456. And Doe 1 testified that Mr. Coulter promised her “a place to stay when she’s old enough.” Id. at 446. A reasonable jury could find beyond a reasonable doubt that Mr. Coulter knew or recklessly disregarded the fact that Doe 1 was a minor—element (3) of child sex trafficking.

b. Conspiring to commit child sex trafficking

To convict Mr. Coulter on the conspiracy count, the jury had to find:

(1) “that ‘two or more persons agreed to violate’ the child-sex-trafficking laws;

(2) that [Mr. Coulter] ‘knew at least the essential objectives of the conspiracy’;

(3) that he ‘knowingly and voluntarily became part of it’; and

(4) that the ‘alleged coconspirators were interdependent.’ ”

United States v. Anthony, 942 F.3d 955, 971 (10th Cir. 2019) (numbers added) (quoting United States v. Serrato, 742 F.3d 461, 467 (10th Cir. 2014)).

In addition to the evidence discussed above, Ms. Andrade testified that she and Mr. Coulter worked together to recruit Doe 1 and that they both facilitated her participation in commercial sex transactions. For example, Ms. Andrade took explicit pictures of Doe 1, and Mr. Coulter used those pictures to entice potential clients. ROA, Vol. III at 608-09. The evidence was sufficient for a reasonable jury to find beyond a reasonable doubt that (1) Mr. Coulter and Ms. Andrade agreed to violate the child sex-trafficking laws, (2) Mr. Coulter knew the objective of the conspiracy with Ms. Andrade was to traffic Doe 1, (3) he knowingly and voluntarily participated in the conspiracy, and (4) he worked interdependently with Ms. Andrade to implement their agreement.

c. Mr. Coulter’s arguments against sufficiency

Mr. Coulter’s arguments are unavailing. He focuses primarily on the credibility of Ms. Andrade and Doe 1. But on review of the sufficiency of the evidence, we do not “consider witness credibility,” a task “delegated exclusively to the jury.” Evans, 318 F.3d at 1018. And as discussed above, the Government corroborated both witnesses’ testimony with ample supporting evidence.

Mr. Coulter also claims he “had nothing to do with [a] sexual transaction between [a client] and Doe 2.” Aplt. Br. at 39. But his convictions stem from his conduct toward Doe 1, not Doe 2. He also disputes a law enforcement officer’s testimony that Mr. Coulter was a member of the “Crip” gang. Aplt. Br. at 40. This testimony was not relevant to the child sex trafficking offense.

B. Testimony about the Deaths of Ms. Diaz and Ms. Biggers

Mr. Coulter contends that the admission of testimony about the deaths of Ms. Diaz and Ms. Biggers violated the Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause, Aplt. Br. at 16, or constituted inadmissible hearsay, id. at 33-34. He also suggests the Government engaged in prosecutorial misconduct by eliciting this testimony and referencing Ms. Diaz’s death in its closing argument. Id. at 28.

1. The Challenged Testimony and Closing Argument

Two witnesses testified about the deaths of Ms. Diaz and Ms. Biggers: Megan Mullins, who formerly worked for Mr. Coulter, and Ms. Andrade, his alleged co-conspirator.

a. Ms. Mullins’s testimony

During the direct examination of Ms. Mullins, the Government asked about how Mr. Coulter disciplined women when they disobeyed him. In response, Ms. Mullins said that when “Lizzy”—Elizabeth Diaz—refused to turn over her earnings, Mr. Coulter physically abused Ms. Diaz and locked her in a closet. ROA, Vol. III at 169.

On cross-examination, Mr. Coulter’s attorney asked, “[H]ave you seen that girl since?” Id. at 200. Ms. Mullins replied, “She’s dead.” Id. Mr. Coulter’s attorney asked when Ms. Diaz died. Id. Ms. Mullins responded, “I think 2011, 2012.” Id.

On redirect, the Government and Ms. Mullins had the following exchange:

Q: You mentioned that Elizabeth Diaz passed away.

A: Yes.

Q: What happened to her?

A: I was incarcerated. From my understanding, she went on a call and she was —

Defense counsel: Objection. Hearsay.

District court: Overruled. You opened the door to this ․ so I’m going to let her follow up. Go ahead.

A: She was found fully clothed like ten days later. They said it was a drug overdose.

Q: All right. What do you believe happened to her?

Defense counsel: Objection. Speculation.

District court: Overruled. I’ll listen to the answer first.

A: I mean, she was killed.

Q: Do you know who killed her?

A: I don’t know.

Q: Do you have someone in mind that you believe was responsible?

A: I don’t know.

․

Q: What did Mr. Coulter say about Ms. Diaz dying?

․

A: We shouldn’t let bad things happen to daddy.6

ROA, Vol. III at 204-06.

Later in the redirect examination of Ms. Mullins, while discussing other women who were associated with Mr. Coulter, the Government asked about Jamie Biggers. Ms. Mullins said that Ms. Biggers had “passed away.” Id. at 210. When the Government asked how this occurred, Ms. Mullins stated that Ms. Biggers “got pushed out of a car on the highway and got hit head on.” Id. at 210. The Government asked, “Who pushed her?” Id. Ms. Mullins responded, “I don’t know.” Id. Defense counsel did not object to the questions regarding Ms. Biggers’s death. Id.

b. Ms. Andrade’s testimony

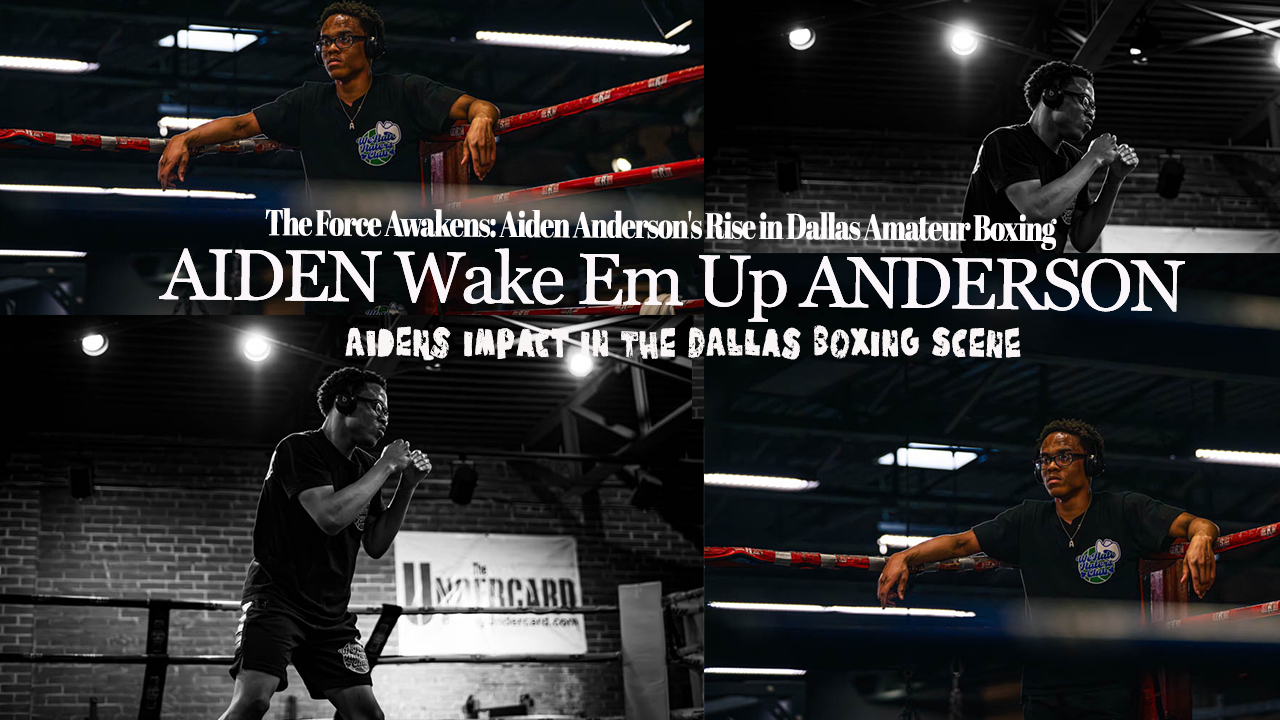

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing

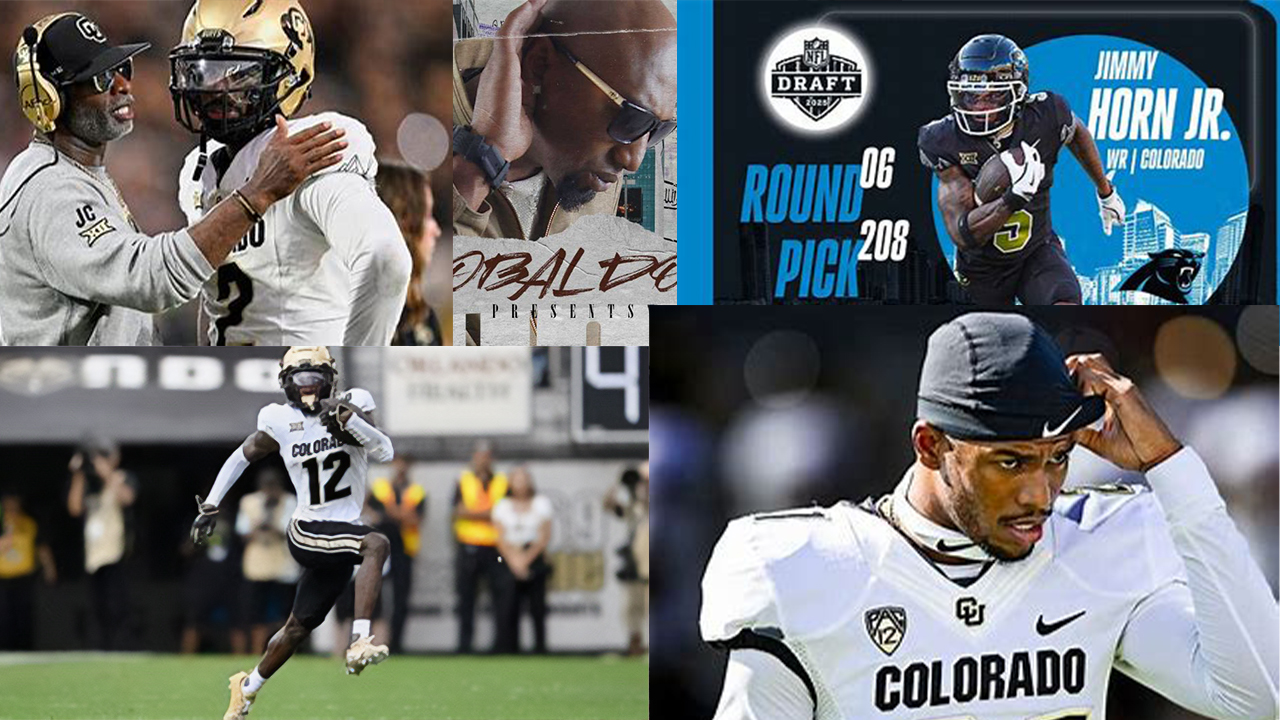

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing  Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more

Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more  Denver Public Schools has resolved to shut down seven schools, facing considerable opposition in the process.

Denver Public Schools has resolved to shut down seven schools, facing considerable opposition in the process.  The Real Spill Talk Show -Overwhelming Friends-

The Real Spill Talk Show -Overwhelming Friends-  SNACO

SNACO  Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert

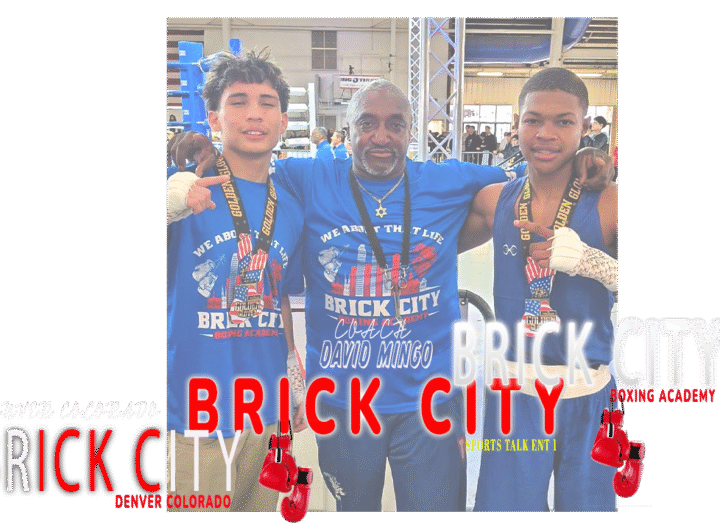

Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert  David Mingo: A Denver Boxing Legend and Community Pillar

David Mingo: A Denver Boxing Legend and Community Pillar  Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities

Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities  Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants

Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants