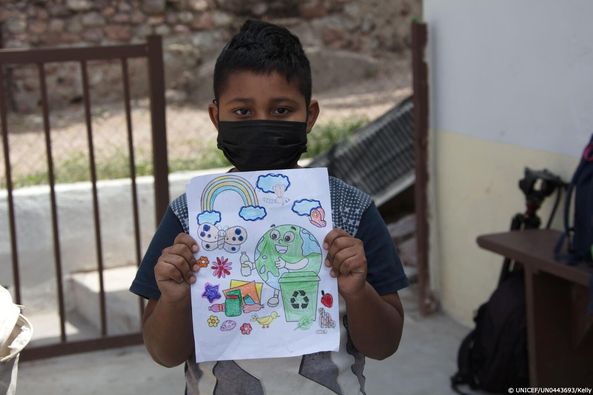

Children show their climate action drawings at a UNICEF-supported shelter for migrant families in Tijuana, Mexico. Since the start of 2021, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are nine times more migrant children in Mexico reaching nearly 3,500 today.

We’re on the ground supporting families and children on the move across Central America and Mexico.

Eitan Peled, Child Migration & Protection Program Manager for UNICEF USA, recently checked in with Rhonda Fleischer, UNICEF Migration Program Specialist, to learn more about how pandemic conditions and a changing policy landscape are shaping UNICEF’s approach to helping migrant children and families stay safe and protected.

Please tell us a little bit about yourself, your professional background and your role at UNICEF.

RHONDA FLEISCHER: I’m a licensed social worker by training. Early on in my career, I worked with runaway and homeless youth, dealing with the child welfare system and working in family-based mental health.

I quickly realized that my passion had a more international focus so that’s when I began what has now been a 20-year career helping refugees in the U.S. Until I joined UNICEF a few years ago, I worked with programs largely funded by the U.S. State Department. I’m really proud of the strong tradition the United States has of welcoming refugees.

Today I work out of UNICEF’s New York headquarters as the Program Specialist for Migration, focusing on the protection needs of refugee and migrant children in the United States. I also support the work in Northern Central America and Mexico, taking a route-based approach in the subregion.

Let’s talk about the larger corridor. You mentioned Northern Central America and Mexico — what is the story for so many of these kids before they actually get to the United States?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Well, we’re talking about some of the most violent places in the world. Violence is a daily reality for children in places like Honduras and Guatemala. They are forcibly recruited into gangs. They’re afraid to go to school. Girls and women are subject to gender-based violence with very little opportunity for justice and protection.

On top of all of that, families have been devastated by natural disasters — hurricanes and floods — in recent years. And now with COVID, conditions are even worse. Domestic violence, child abuse and infanticide have all skyrocketed.

The other thing that’s important to mention that’s pretty unique to this part of the world is how much this really is a family reunification issue. So many unaccompanied children who seek to come to the United States are really looking to reunite with parents or other close family members that are already living here. The violence, devastating natural disasters, poverty — these are some pretty compelling drivers that are forcing people to leave places they love and that they call home. There’s an impetus to think, ‘Well, my mother is in the U.S., and I’ve been wanting to see her for seven years now.’

So what happens once a child arrives at the U.S. border, and what is UNICEF’s role in that process?

RHONDA FLEISCHER: Generally when children or families arrive at the U.S. border, they’re detained by Customs and Border Protection. They’re supposed to spend no more than 72 hours in detention, and then be released. Families are generally either put into a family detention center or released to one of the many shelters run by community-based organizations along the southern border.

If it’s an unaccompanied child, the child is turned over to the care of a shelter within the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In that system, the government looks to identify a parent or other family member to whom they could release that child while the child’s immigration proceedings continue.

For families, there really hasn’t been a robust formal system to date, a formal family case management program or other type of option to support those families to make their way from that point at the border to the communities where they’re destined.

There is, however, an amazing, heroic bunch of volunteers and staff working with community-based organizations who have rallied to support families as they make their way into local communities and hopefully have a chance at a fair process in immigration court.

Even before the pandemic, UNICEF was concerned that policy changes had made it very, very difficult for children and families to access the U.S. border, or to seek legal pathways that would allow them to avoid the dangerous journeys to come here. And then in March 2020, more restrictions were put into place that effectively stopped asylum processing at the border for most people — and thousands and thousands of children and families were expelled without due process. Basically since COVID the U.S. has not allowed vulnerable children and families to seek protection, pushing them back into harmful situations.

Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants

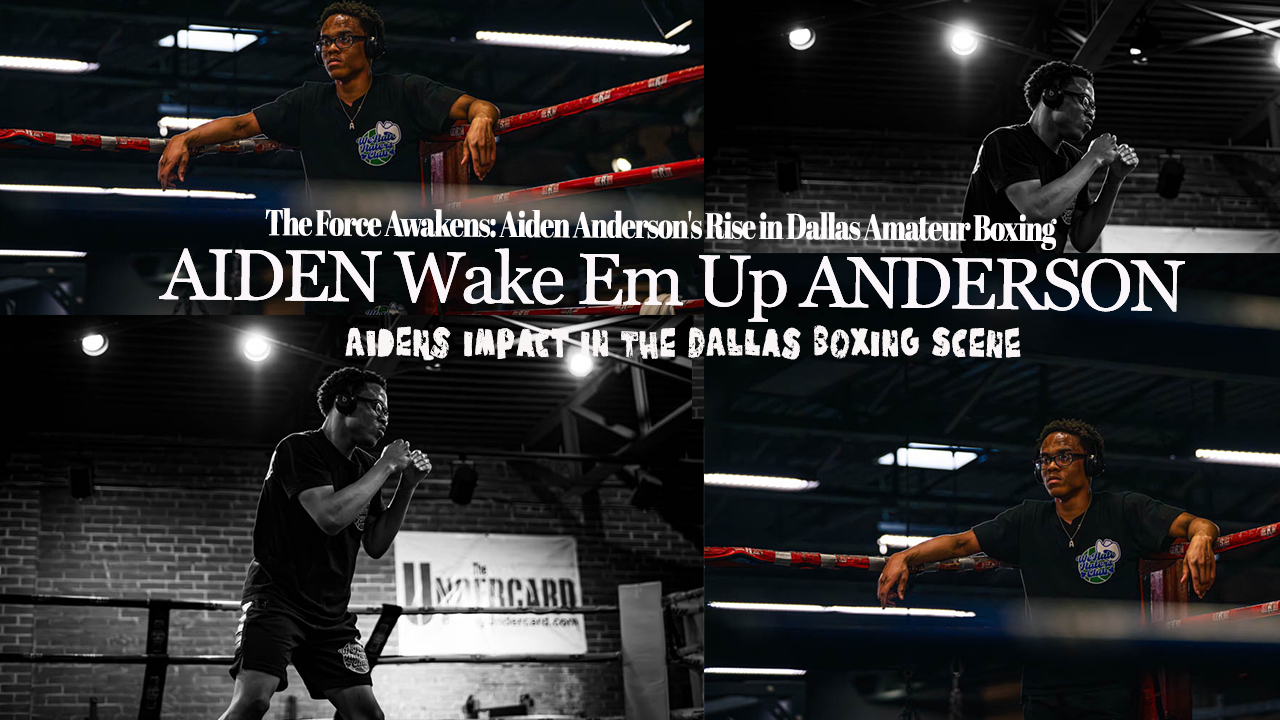

Trump administration offers to pay plane tickets, give stipend to self-deporting immigrants  The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing

The Force Awakens: Aiden Anderson’s Rise in Dallas Amateur Boxing  Tesla’s Cybertruck Will Rapidly Depreciate From Now On

Tesla’s Cybertruck Will Rapidly Depreciate From Now On  Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert

Was it really about the Lil Wayne Concert  Black Chicago Activists Blast Mayor Brandon Johnson for “Replacing” Them With Migrants

Black Chicago Activists Blast Mayor Brandon Johnson for “Replacing” Them With Migrants  Migrants desperately digging through trash bins for food as they live out of buses in Chicago

Migrants desperately digging through trash bins for food as they live out of buses in Chicago  Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities

Sofia Llamas: A Force for Good in Colorado – Igniting Hope and Empowering Communities  Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more

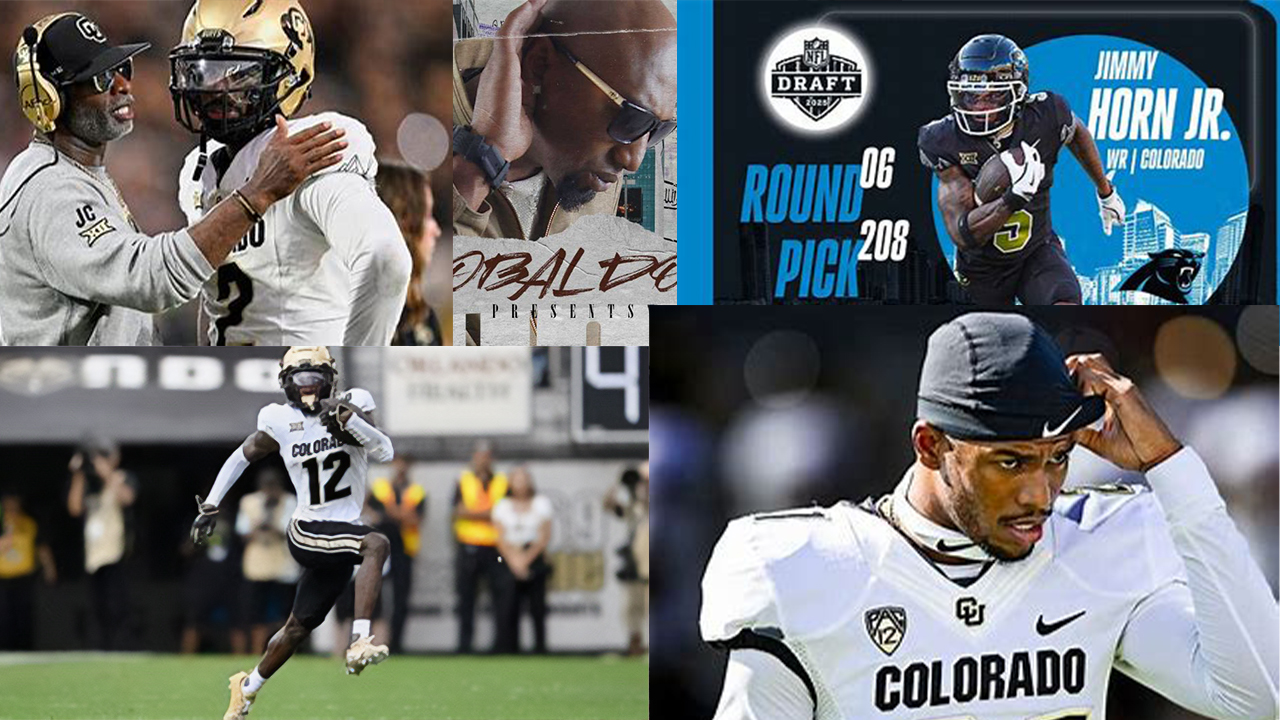

Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr, Shedeur Sanders, Travis Hunter, Shilo Sanders, Jimmy Horn Jr, Global Don, and more